Prologue

This review is late in coming, as the book A City on Mars was released on November 7, 2023. Despite having pre-ordered it from Amazon and being an Amazon Prime customer, I had one slight problem: Amazon is “first come, first served” and by “first,” Amazon means “America first, baby!” I live in France, so I waited months for my next-day delivery. Also, I’ll handle the review by summarizing a few of their key points. Where citations are not present, they’re in the book.

Anyone who knows me knows that I love space and I’ve even given talks about the topic , so I feel like I’m fairly well-read on the subject. In fact, at the last talk, despite wearing my “Occupy Mars” polo and being a huge proponent of space, I said:

To be honest, with the ethical, financial, legal, political, engineering, and scientific challenges, we will not be colonizing Mars within the next generation or so, though the moon’s actually interesting.

I was so, so wrong. We won’t be colonizing the moon or Mars within my lifetime (or yours). We might get more-or-less permanently manned scientific stations on the moon and we might get boots on Mars, but people won’t be going to either of those places to live.

The Premise

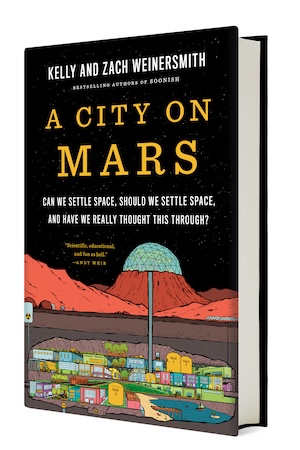

The book “A City on Mars” is written by the wife and husband team, Kelly and Zach Weinersmith. Dr. Kelly Weinersmith is adjunct faculty in the biosciences at Rice University who studies parasitic manipulation of host behavior. Zach Weinersmith draws funny pictures . For this book, they actually set out to write a book explaining how we were going to colonize space. Both of them are huge fans of space. However, as they did their research, they kept hitting problem after problem. Five years later, they (perhaps somewhat reluctantly), produced a book explaining why we not only won’t be settling space in the near future, but why this is possibly a good thing. Their list more or less matched my own, but despite my being well-read on the topic, their knowledge dwarfs my own. They even killed my thoughts on our first rotating space stations.

Despite the Weinersmith’s obvious delight in grinding my dreams under their collective heels , the book is a joy to read. It’s well-paced, hilarious, and the arguments are well-researched, with a thick bibliography in the back of the book. But don’t take my word for it. Of the many glowing reviews, this one stood out to me.

Of the many books and extensive literature on space-mission architectures, technical and otherwise, this is the only one that is a must read to understand the deep financial, physiological, and technical constraints of one of the largest and most ambitious endeavors of our time: enabling humans to become a multiplanetary species.

When you have members of the Advisory Council of the European Space Policy Institute recommending your pop-sci book, that’s some pretty heavy-duty street cred.

Which brings us to the obvious question: what are they arguing? My list of objections seemed kind of long, but they sailed past them, waving merrily as they covered far more ground than I ever imagined. Clearly in a short review, I won’t cover them all, but I’ll touch on some highlights and start with some important questions for understanding if we might colonize space.

The Space Settlement Questions

When it comes to the possibility of humanity settling space, it’s sometimes framed in the context of two questions.

- Will a space settlement have enough local resources to survive?

- Will a space settlement be financially self-sufficient?

If the answer to both of those questions is “no,” we can kiss space settlement goodbye. If the answer to both is “yes,” get your radiation-hardened suitcase ready. If the answer to one is “no” and the other is “yes,” depending on which way it goes, we’ll have radically different space settlements.

Those are great questions, but they’re not enough.

Ethical and Scientific Issues

There are several questions missing from the previous ones, which this book makes clear, but I’ll just touch on two.

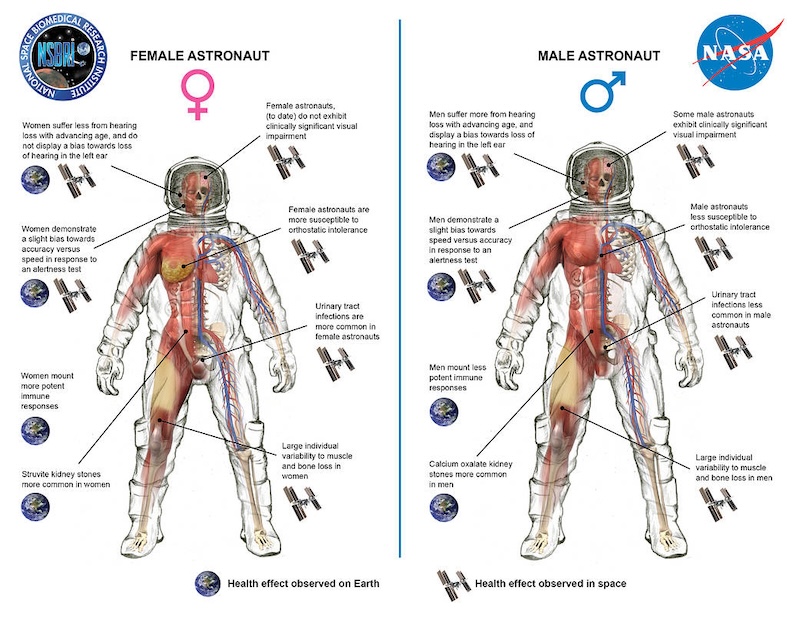

- Can humans survive in micro- or low-gravity environments long-term?

- Can we have babies in those environments?

We might naïvely assume we have the answer to the gravity question, but we don’t. Astronauts, cosmonauts, and taikonauts living on space stations do so for relatively short periods of time. Further, they’re on stations protected from most radiation by the Van Allen belts . We simply have no information here. You might think we can just throw a bunch of people on Mars and hope it all works out, but that’s ethically dubious, at best.

Even if they know the risks they’ll be taking are considerable, potential babies (gotta have babies if you want a colony), won’t know, or agree to, those risks. Can we conceive on Mars? Will the embryos be healthy? Will the children be able to grow into adulthood? Even if they grow up to be adults, if there’s a catastrophe, will they be physically capable of returning to Earth, or have we doomed them to exile?

Oh, and let’s not forget that Mars is covered in perchlorate. Perchlorate inhibits the thyroid hormone. We can treat this.

It also appears to affect brain development in children, starting at the embryonic stage. We cannot treat this.

We don’t know the answers to any of these questions and even if adults agree to the risks, we can’t accept the potential horror of raising a generation of underdeveloped children with learning disabilities, or worse, severe brain damage.

The only way we can get the answers to the “space babies” question is doing generations of micro- or low-gravity research with smaller animals before we work our way up to anything remotely analogous to humans. And we’ll need control groups, and have some of this research happen outside the Van Allen belts. Oh, and don’t forget to factor in the perchlorate exposure.

But who’s going to pay for this? I can’t imagine US taxpayers will be keen on spending billions of dollars on multi-generational studies of lab rats having sexy time in space. Will corporations? Maybe. If they can turn a profit. And while people might not be upset if mice don’t survive this, imagine the PR nightmare of breeding primates in space, only to have cute little monkey babies with severe brain damage.

But we still have to do this. Dodging ethical questions by ignoring them is ... checks notes ... bad.

From my perspective, I also think we need to consider what our response should be if we discover extant life on Mars. Though it’s a distant possibility, native life might exist on the Red planet. If so, any plans on colonizing Mars need to grind to a halt while we consider the moral and scientific questions that would arise. The Wienersmiths only touch on this briefly, on page 146, but given how unlikely life is on Mars, this is hardly a critique.

Can Mars Turn a Profit?

OK, so there is some medical research we have to do, but we can make a profit off of our colonies, right? For Mars, that’s very unclear. Sure, Musk has a plan to send people to Mars with ticket prices as low as $100,000 , but he views SpaceX as a transportation company. It would be up to the aspiring colonists to do almost everything else, including being self-sustaining.

But how are they going to do that “everything else” if they can’t pay for it? Space geeks like to claim that the settlers will be incredibly resourceful and come up with plenty of intellectual property they can sell to Earth.

Bullshit. With even our limited understanding of what it takes to build and maintain a self-sustaining environment, those settlers are going to be working 10- to 12-hour days just trying to stay alive. Farming, cooking, cleaning, exercising, monitoring life support, and constantly repairing the habitats will be most of their day, with maybe a little exploration done on the side. And any “colony” will be so ridiculously small that it’s hard to imagine they’ll have significant intellectual capital to sell back to Earth. Musk has said that colonists will have free trips back to Earth. I think he would be surprised at how many take him up on that.

And no, they’re not going to be shipping tons of physical goods back to Earth, either. There’s not much that’s apparently valuable on Mars that we can’t make or find cheaper on Earth.

A Colony on the Moon?

What about the moon? Helium-3 is incredibly valuable and plentiful, right?

Nope. Aside from some obscure medical uses, helium-3 is only valuable to us for fusion energy. For a fusion reactor we can’t build. A more advanced version of the fusion reactors we have failed to build for decades. And how would we get that helium-3 on the moon? It’s only in a concentration of a few parts per billion and we’d be strip-mining the surface of our satellite. Oh, and we’d have to build and maintain huge mining and processing facilities, along with mass drivers to launch them from the surface. All of those would have to withstand the intense radiation and the extreme high and low temperatures of the lunar day-night cycle. All to harvest something for a reactor we don’t have and we’re not even sure we can build.

It should be noted that, if it works, the payoffs could be huge. According to the paper Nuclear Fuel Resources of the Moon: A Broad Analysis of Future Lunar Nuclear Fuel Utilization , we might have enough helium-3 to provide anywhere between 500 to 1,400 years of Earth’s total energy consumption ... if we were to strip mine the entire surface of the moon about three meters deep.

Brilliant plan, eh?

So, what about the water? There’s enough for a small lake. When it’s used up, it’s done.

To add insult to injury, you can forget about harvesting carbon or nitrogen on the moon, meaning that the elements which are, um, critical for life and building and maintaining an ecosystem, aren’t there. We need to ship them in. The moon will be a money sink, not a money source.

That’s OK if we’re committed to make that effort, but scaling up to a colony? Not gonna happen in our lifetimes. Small science stations? Sure, but that’s about it.

Let’s Live on Space Stations!

So at this point, we’re pretty much left with space stations. No O’Neill Cylinders, but maybe we can get a Stanford Torus ?

The answer is “no.” To build a large enough station for people to settle on—something even remotely close to our sci-fi dreams—, we have to consider the mass of the structural material, the water, the soil, the atmosphere, and so on. It’s going to be millions of tons of mass, and we’ll also need to consider the logistics and construction.

It’s easy to do the math and try to figure out the number of rocket launches from Earth to launch enough rockets to build the station, but it becomes clear that even with the upcoming Starship, it’s not feasible to launch from Earth. So we need something in space (probably the moon) which launches much of the raw material towards where we want the station built, and something at that location to catch the material. We really don’t know how to do that, and that’s before we consider that we don’t know how to build a large, self-sustaining radiation-hardened hamster wheel.

Remember those first two space settlement questions above?

- Will a space settlement have enough local resources to survive?

- Will a space settlement be financially self-sufficient?

There’s a good argument to be made that the answers are “no” and “no” for a Stanford Torus, but by the time we have the engineering ability to construct one, perhaps we’ll have enough of a space industry where those answers will change. For now, it’s simply not possible, and probably not possible for the foreseeable future.

Verdict?

This is a damned amazing book. It’s hugely informative and very funny. Weighing in at almost 400 pages, with an extensive bibliography, it’s clear that this review barely scrapes the surface of what’s in there. I didn’t get a chance to talk about the legal and political issues. Or the space sex. Or the space cannibalism. You know, the parts you’re dying to read about.

If you, like me, have the slightest interest in what it will take to become a multiplanetary species, this is the book you should buy